As our current cultural reckoning rushes to canonize once-fringe artistic practices, some have stood out for their impressive prescience. Linder has been a cult favorite since the 1970s when she burst onto the scene as front-woman of the post-punk band Ludus and gained recognition for her sharply satirical photomontage. One classic example, a naked woman with a clothes iron for a head, appeared on the cover of English punk rock band Buzzcocks’ 1977 debut single “Orgasm Addict.”

Today Linder is recognized as one of the foremost feminist artists of her generation, and her sprawling practice includes photomontage, drawing, photography, and performance. “I’ve conducted a half century enquiry into photographic images of sex, fashion, food and lifestyle,” Linder said in an email interview with me. “Collectively, we seem far more obsessed than ever in ‘curating’ our lives, our wardrobes, our mascaras even.”

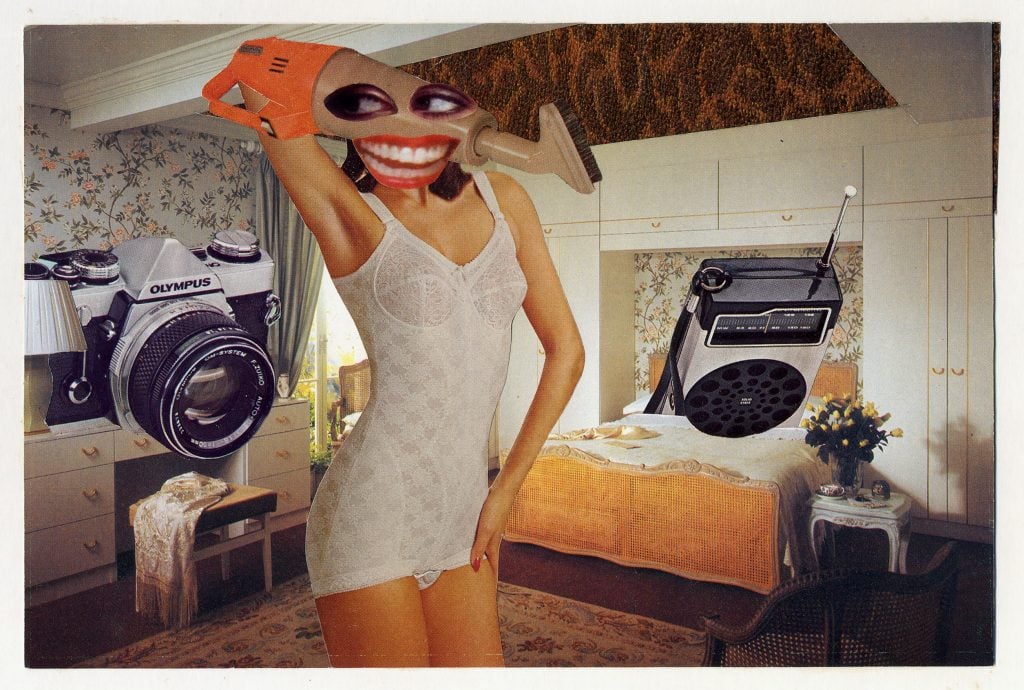

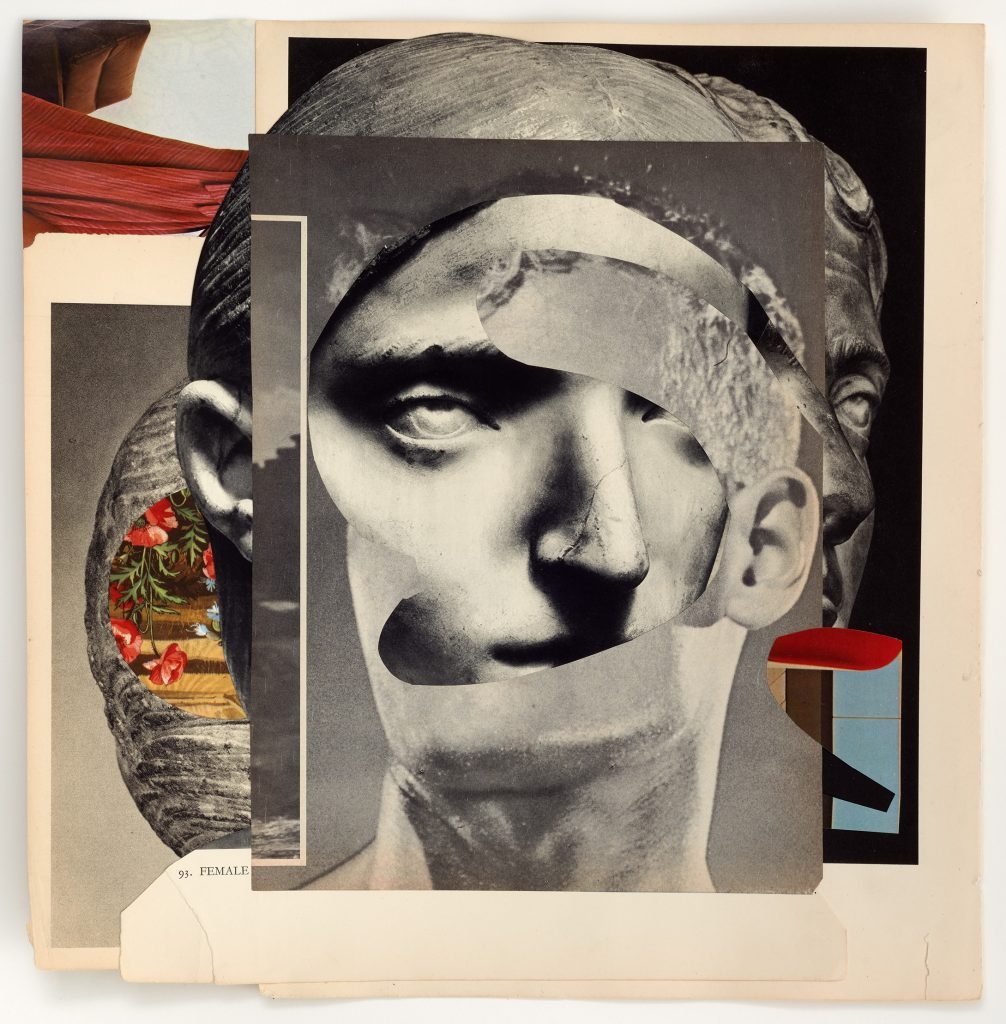

Linder, Untitled (1977). Image: © Linder, courtesy of the artist and Modern Art, London.

In recent years, Linder was the subject of the solo exhibitions “The House of Fame“ at Nottingham Contemporary in 2018 and “Linderism” at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge in 2020. Her work was contextualized within the wider ambitions of a proudly riotous cohort of women artists in Tate Britain’s 2023 survey, “Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the U.K. 1970 – 1990.” She will have a retrospective at the Hayward Gallery in London in early 2025.

In an untitled 1977 work, an underwear model poses next to a huge hovering camera in her bedroom. Her face and arm have jointly morphed into a vacuum cleaner, but the wooden posture of her bronzed body is no more convincingly corpulent than the machine’s. Instead, it has the rigid pliancy of a doll. “It’s not so much that I’m a camera, to quote Christopher Isherwood, it’s more that I stare through the lenses of others with curiosity, wonderment, confusion, and sometimes outrage,” she said. “I then use my surgeon’s scalpel and work deftly to cut away all that is superfluous in a photograph so that it ‘tells in a new way’ to quote [British art historian] Dawn Adès.”

Linder, Untitled, 1977. Image: © Linder. Courtesy of the artist and Modern Art, London.

Chopping up all manner of visual ephemera to be reassembled in apparently random yet, in some other sense, related arrangements that create new meanings? It could describe online meme-making today, or even the experience of swiping through apps like Instagram or TikTok. Now, as then, curated collage remains one of the more accessible ways to produce commentary on our culture.

Linder at the Hayward Gallery. Photo: Hazel Gaskin. Courtesy the artist and Hayward Galler

Linder’s own much cited precedent lies in the experiments of Hannah Höch and other Dadaists, whom she admired for how they “used humor to make their point in the gravest of times.” These avant-garde pioneers lived in post-war Germany, where the hope promised by modernity had curdled into horror. It is little wonder they embraced absurdism, a tool just powerful enough to cut through the era’s sense of nihilism.

“I’m from Liverpool and it’s a very quick-witted city,” said Linder, on why this approach felt like second nature to her. “Why labor a paragraph to prove a point when a one liner will do? Why spend months with tubes of oils and watercolors when a magazine and scissors are to hand?”

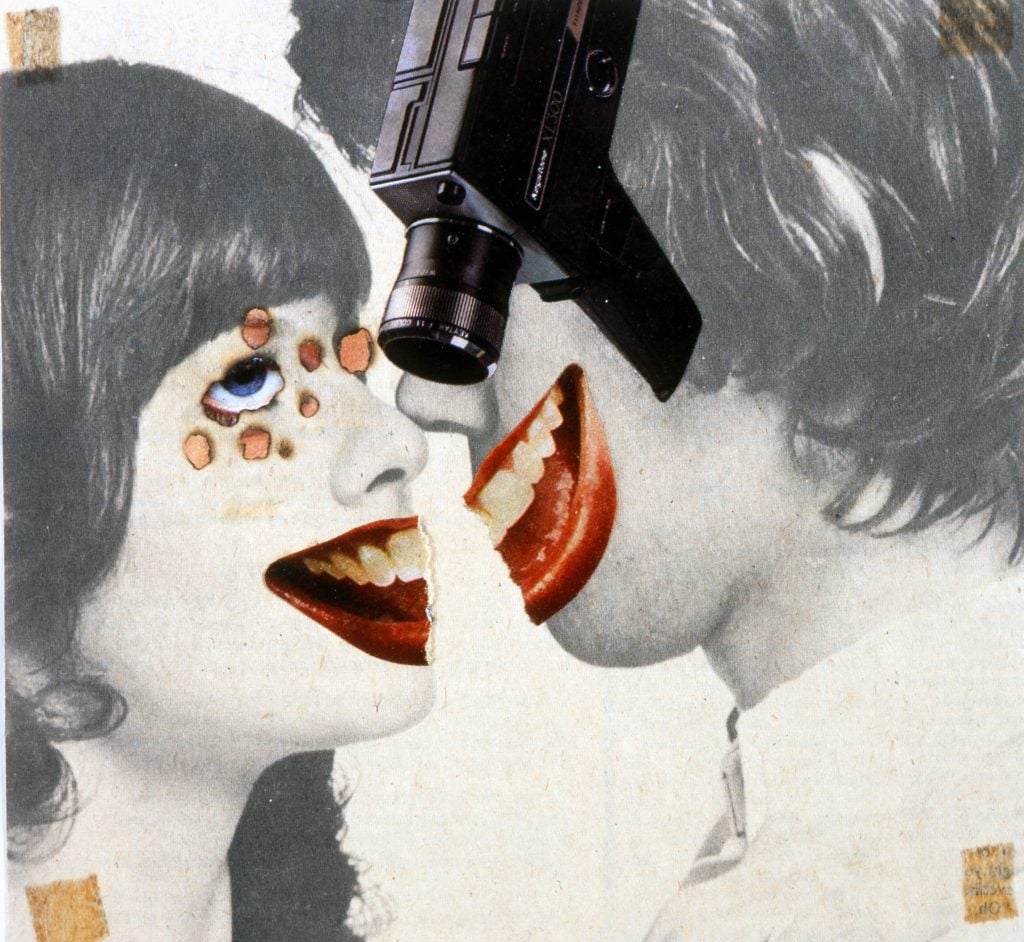

Linder, SheShe (1981). Image: © Linder, courtesy of the artist and Modern Art, London.

She was born in Liverpool in 1954 as Linda Mulvey but changed her name while studying graphic design at Manchester Polytechnic. At around this time she befriended Morrissey, soon to be front-man of The Smiths, at a Sex Pistols gig and became heavily involved in Manchester’s underground punk scene. Most memorably, in 1982, Linder wore a dress made of raw meat during a performance by Ludus at the legendary Haçienda nightclub. The stunt was a protest against both the sale of meat products and the venue’s custom of screening pornography. Packages of meat wrapped in explicit imagery were handed out to the audience and during the final song Linder whipped off her skirt to reveal a 12-inch strap on.

Provocations like these that drew attention to the commodification of women’s bodies would reappear throughout Linder’s five-decade practice. For the SheShe series, she re-enacted “a mode of claustrophobic self-obsession,” by wrapping herself up in cling film, bandages, and cut-out images of other women’s mouths. “So many people around me were self-harming then,” she explained, “I was one of the lucky ones in that I used a blade to cut up magazines rather than cutting up my forearms.”

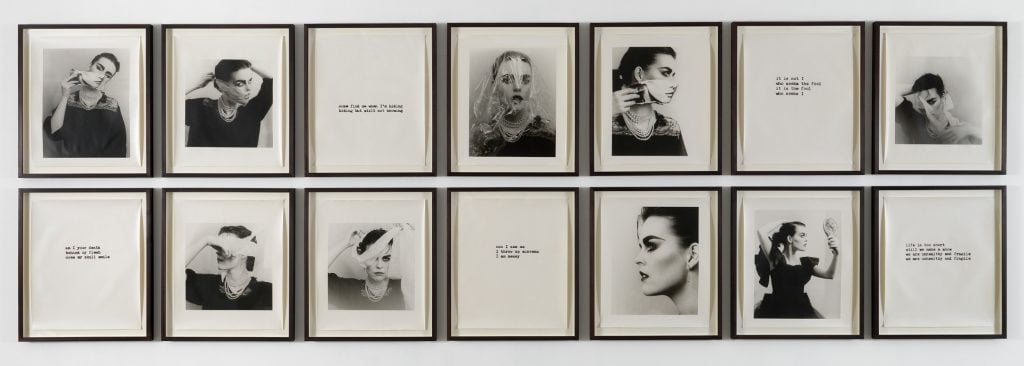

Linder, Untitled, 1979. Image: © Linder. Courtesy of the artist and Modern Art, London.

Performance art has been a component of Linder’s work since her Ludus years and continues to inspire her. It rouses “extraordinarily liberated states of creativity,” in particular music and dance as “the perfect antidotes to the very solitary act of photomontage.” For the Hayward show, she is collaborating with the choreographer Holly Blakey on a new ballet performance that will take place at Southbank’s Queen Elizabeth Hall and later travel to the Edinburgh Arts Festival.

“A thread throughout Linder’s practice is looking at the self, looking at identity, and how we can not conform to that,” said the Hayward’s chief curator Rachel Thomas. “If you look at her early work, the DNA of her practice—surrealist juxtaposing of found images that question societal norms—the new work questions again the relevance of the body in art and how that’s constructed today in digital media and on the internet. Linder brings that up to date.”

Linder, The Sphinx, (2021). Image: © Linder, courtesy of the artist and Modern Art, London.

The Hayward retrospective will be a rare opportunity to view early works that have become very fragile. “the glues that I used are slowly devouring the images over time,” she said. “The newsprint in many of the 1970s works has now yellowed.”

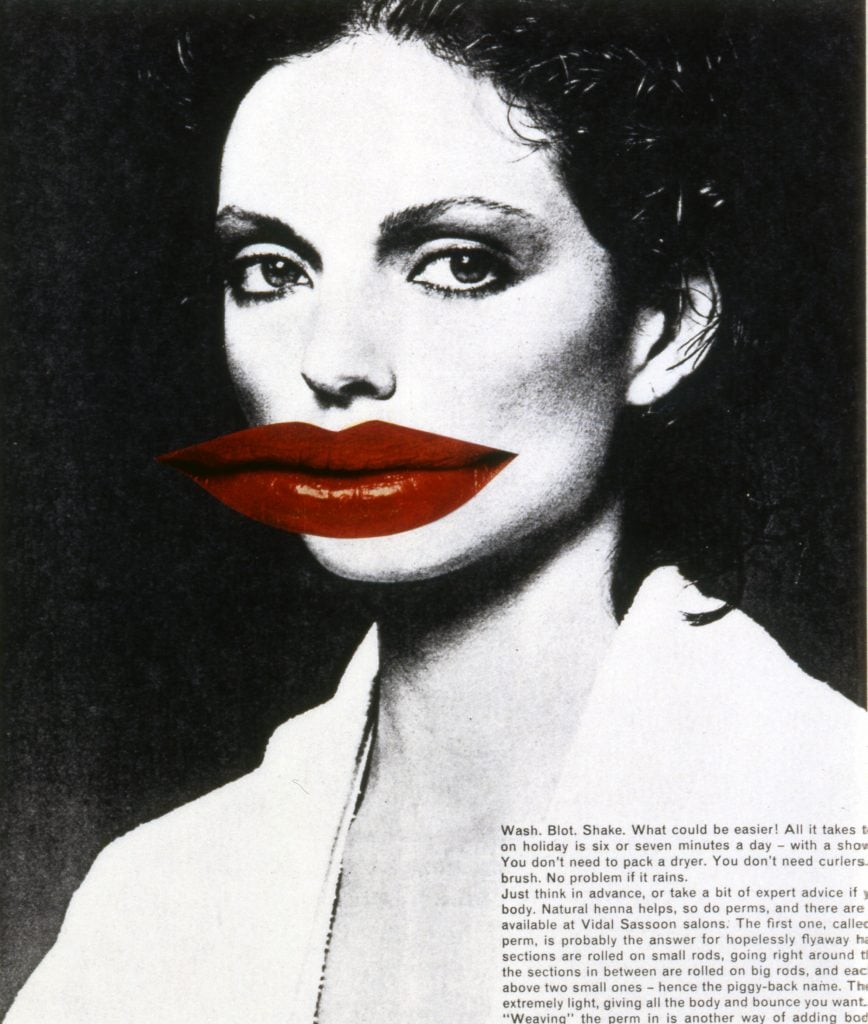

The exhibition will also foreground “glamor” as a guiding theme for Linder, though today the term is defanged of its once subversive power.

Linder, Superautomatisme Ballets Russes I (2015). Image: © Linder. Courtesy of the artist and Modern Art, London.

“Over the centuries, many have been accused of witchcraft and hung for ‘throwing a glamor’,” she explained. At the Pendle witch trials in 1612, ten people, mostly women, were found guilty and hung “because of a kind of glamor about them.” Linder’s practice has done “its best to hold an awareness of the allure and dangers” of glamor. “Harrison Marks is credited with inventing the phrase ‘glamor photography’ in the late 1950s. I’ve cut up and reconfigured Marks’s glamor photographs many times, sometimes amplifying the glamor and at other times muting its thrall.”

Linder has continued making photomontage though some of her methods have changed, as in the case of The Sphinx (2021). “I’ve liberated my cuts so that they no longer faithfully follow the outlines of each motif,” she said. “I sometimes use large cumbersome scissors now as an ‘objective hazard’, to quote the surrealist Ithell Colquhoun. I invite chance and an absence of control into my process far more often now.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: