Geraldo Gonzalez, also known as the “King of Transit,” knows local public transportation like the back of his hand. He knows the route numbers, the schedules and the types of buses.

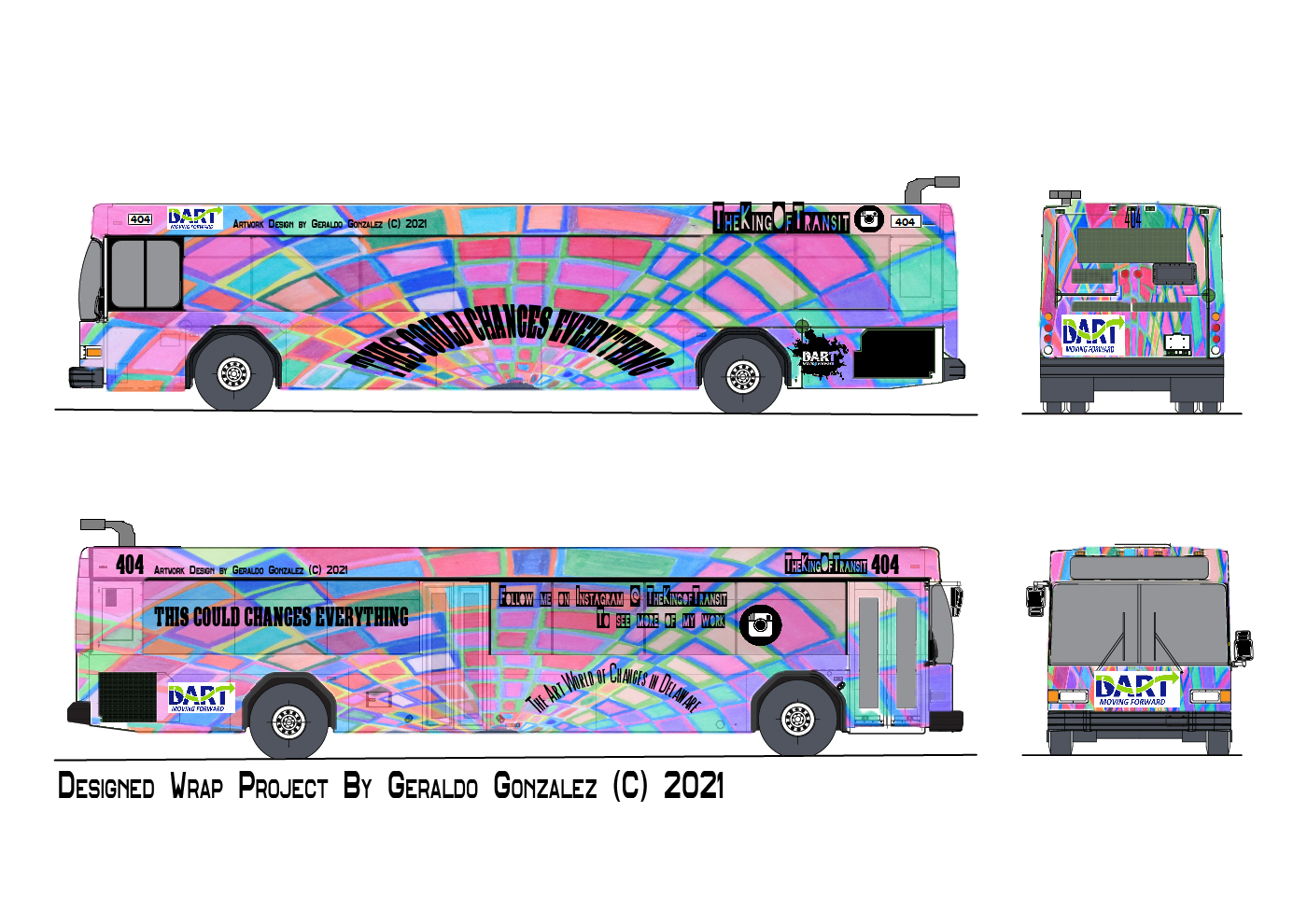

For more than 20 years, the 35-year-old artist has put his enthusiasm for transit into making art. Gonzalez’s most recognizable work is what he calls technicolor or psychedelic design — bright, bold works of art. A run-of-the-mill DART bus, a turnstile or train, transformed.

The artwork starts with photos. Lots of photos. Gonzalez spends a lot of time photographing public transportation.

To create an enlarged line drawing from the photograph, Gonzalez developed his projection technique. The bright colors aren’t painted on but added with colored pencils.

Sometimes, the photos themselves are transformed. Photoshop Lightbox is a fixture of Gonzalez’s photographic art. One technique, which he explains in a Medium post, is creating a digital bus wrap by removing existing advertising in the photo, building a mask and adding whatever artwork he wants to the bus.

An artist from a young age

Gonzalez started photographing buses back in 2002, at age 13, he started taking photographs at the DART bus garage in Wilmington.

“They would have some old buses ready to retire,” Gonzalez, now 35, said. “I’d just grab my camera and snap pictures before these old buses would fade off, out of service, so I can remember the buses that I rode in the past.”

He didn’t think of it as art. He wouldn’t become an artist for another couple of years — in fact, Gonzalez remembers the exact date he became an artist. On Friday, September 17, 2004, he saw an announcement for a DART transit student poster contest.

Geraldo Gonzalez as a teenager. (Courtesy)

Gonzalez was a student at Christiana High School, and still a transit enthusiast. He started drawing that day and later walked over to the DART Corporation office on the Riverfront to show his work.

He met managers and marketers who talked to him about the contest and took pictures of him with his drawings. It wouldn’t be until 2006 that he would win the contest, after two years of improving his drawing skills and picking up a camera again, this time when he incorporated photographs into his art.

Becoming the ‘King of Transit’ despite the obstacles

Every day after school Gonzalez would head to Rodney Square, then a downtown transit hub, and photograph buses for his artwork. He would send his art to transit companies all over the country, and many would respond, sending him swag and notes saying they’d hung his art in their office.

He called himself the King of Transit.

Gonzalez felt confident that his art could be in a museum. He quickly found that walking into the Delaware Art Museum cold and asking if they’d show his art wasn’t going to work.

He knew how to make art, but he didn’t know how the art world worked and he struggled to be taken seriously.

Sometimes, he would run into trouble with law enforcement when he was photographing buses and trains. As a young Taíno with a camera, he was stopped often, no one quite believing that he was an artist. Despite support from people in the transit enthusiast community, that took a mental toll.

The Creative Vision Factory pushed Gonzalez to the next level

In 2011, things started to change. Through a neighbor, Gonzalez met artist Michael Kalmbach, who was putting the pieces together to open the Creative Vision Factory (CVF), a peer-to-peer nonprofit supporting people on the mental and behavioral health spectrum in a studio art environment.

CVF opened in December 2011, and Gonzalez became one of its first members. He had his first exhibition there in February 2012. With this new studio space and support, he committed to creating five works a day. By 2019, he succeeded in winning a Delaware Division of the Arts Grant for the first time. His work has been shown in multiple cities in the region and beyond.

In 2023, Gonzalez joined the Delaware Art Museum’s Public Art Stewards Training Program, a six-month workforce readiness program that trains Public Art Stewards to clean, conserve, and document public art funded by the American Rescue Plan Act.

It all came after a lot of work and a lot of challenges. His successes demonstrate the deep need for programming like CVF, which gives space and support to community members who are often ignored, feared and misunderstood.

Now, as the Creative Vision Factory goes through a location change after months of its own challenges, Gonzalez has moved on independently, while continuing to support the program that supported him for more than a decade. He has his own studio and lives in Cool Spring Park, where he balances art, culture and a job at ShopRite. His dream job, though, is something else.

“Working for a bus company,” Gonzalez said, “that’s my future job.”